Cpt Security Sparrow's App Shop - iCTF2015 Writeup

The last year’s iCTF organizers changed the format of the event regarding vulnerable services. This time the services to be exploited were not provided by Vigna and Team Shellphish but had to be submitted by the participating teams. Even though we had only a few weeks for preparations we were thrilled to face the challenge. Shortly after collecting some ideas we began hacking down the first prototype of our service. Over time the tinkering evolved to a solid service, ready to be broken by teams over the globe. Service specification provided by the guys from Santa Barbara offered two general possibilities to implement the services. It could have been a xinetd or a web based service. We made the choice to implement a web application based on the Python microframework Flask and a corresponding Android app. The general idea was to force the attackers to deal with both, the web app and the Android app. The actual functionality, you probably already guessed by the name, is an app shop to provide next generation security software. Circumventing a small obstacle the attacker can gain access to a closed area on the website to download an interesting app. The app communicates with our website, to be precise a web service, implementing two factor authentication inspired by hard or in context of smartphones increasingly popular soft tokens. The difference between our InsecureID and competitors’ products is that we managed to create a solution which is not only secure but also easy to use ;-)

Web Application/Service

If you’re familiar with frameworks like Sinatra or alike you will feel at home with Flask. It’s a Python microwebframework in which methods can be equipped with a decorator to bind it to a certain URI and a request type. Consider the following code for user creation.

@uss_app.route('/createuser', methods=['POST', 'GET'])

def createuser():

if request.method == 'GET':

return render_template('createuser.html')

elif request.method == 'POST':

user = request.form['user']

password = request.form['password']

if is_invalid_user(user):

return render_template('error.html',\

error_msg='Arrr, go away, you monkey'), 400

# [...]

return render_template('login.html')Access to the HTTP methods and parameters is given through the request variable. Afterwards the response content and the status code (default 200) is returned as a tuple. In case of a web service it makes sense to return just the expected content (like JSON). When using a web page you should make use of the template engine to separate the views and the logic. This should be enough information for you to dig through the code by yourself. When visiting the site you are presented with a short company profile and some news underneath. Old job offers give you some hints about topics involved in the challenge. The most interesting news is of course the launch of UnsecurID for invited customers. And you are so not invited…

You have to visit the customer area with a created and logged in user, obviously. At this point you’ll notice that you’re not one of those fortunate who can use UnsecurID. Digging inside the code you will find the solution which enables you to elevate privileges. Inside the HTTP service service/www/uss.py the is_valid_customer() method is called during the login. It checks if the username contains the string “customer”, nothing more. So the next step towards the solution is to create a user with the respective name. Now the customer area looks different. Digging further through the code you will find multiple methods which don’t render HTML but instead respond with some text or JSON. The functions _set_flag() and get_flag() are reserved for use by the event organizer to be able to check whether the service is running. The interesting ones are get_token() and get_time(). The latter accepts a FLAG_ID, which is given by the organizer respectively their iCTF-Framework . This information along with some random value and the current server time is used to create a SHA224 hash, which is returned afterwards. This is a very ugly way to make sure that the exploit has to talk to the mothership. This measure and the hash changing every minute prevents the attackers to reverse the obscure crypto once and use it for every token without exploiting any vulnerability. One has to be at least polite enough to execute the whole pseudo crypto. get_token() expects the FLAG_ID and a calculated secret(whose generation will be explained at the end in detail). The method checks if one is a valid user and entitled to use the UnsecurID app. Afterwards the time stamp is generated again locally, taking FLAG_ID into account. The received secret is base64-decoded and then XORed with the time stamp. The SHA224 hash of the result is compared with a globally stored hashed_secret afterwards. Though the hashed_secret resides inside the web app it can’t be used by attackers to calculate the secret, except if they are in the position to revert/brute-force the hash (which I doubt). So there’s a missing piece of the puzzle and the only thing left to look into is the Android app.

Android App

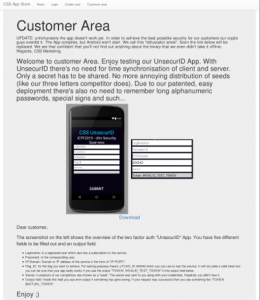

After you created a valid account you are in the position to download the actual app (and to make requests to the web service in order to generate flags). The download page holds a lot of information and hints. The first sentence, for some people disappointing, states that the app is obfuscated in a manner that it can’t be run by the Android Emulator. So decompilation and static analysis is the only way to reverse the app. The following screenshot shows the app along with some explanations.

The fields username and password are self explaining. The SERVER/IP enables communication to your instance of the Cpt Security Sparrow’s web service. Then follows the FLAG_ID, which is given by the iCTF-Framework. And of course the secret you have to find out by yourself. The binary APK available for download is obfuscated to make your life harder. You can decompile it into smali . Or convert it to a JAR and use a Java decompiler like JD-Gui or Luyten. To give an overview of the functionality I will use the original source code. Otherwise the post would be a lot longer. A link to the code is attached bellow. So you can have a look at the original code and if you wish reproduce the obfuscated binary APK using ProGuard. As for that matter you find a commented proguard-rules.pro file inside the Android-Studio project.

The functionality of InsecurID (often referred as UnsecurID) is split into four classes. The lib.HttpRequests class is a publicly available wrapper by Kevin Sawicki around Java’s uncomfortable HTTP client API. The view and its logic inside the MainActivity class are not entirely uninteresting. It contains the general logic of the program flow and is additionally interesting due to the error messages. Consider the following snippet.

The fields username and password are self explaining. The SERVER/IP enables communication to your instance of the Cpt Security Sparrow’s web service. Then follows the FLAG_ID, which is given by the iCTF-Framework. And of course the secret you have to find out by yourself. The binary APK available for download is obfuscated to make your life harder. You can decompile it into smali . Or convert it to a JAR and use a Java decompiler like JD-Gui or Luyten. To give an overview of the functionality I will use the original source code. Otherwise the post would be a lot longer. A link to the code is attached bellow. So you can have a look at the original code and if you wish reproduce the obfuscated binary APK using ProGuard. As for that matter you find a commented proguard-rules.pro file inside the Android-Studio project.

The functionality of InsecurID (often referred as UnsecurID) is split into four classes. The lib.HttpRequests class is a publicly available wrapper by Kevin Sawicki around Java’s uncomfortable HTTP client API. The view and its logic inside the MainActivity class are not entirely uninteresting. It contains the general logic of the program flow and is additionally interesting due to the error messages. Consider the following snippet.

//[...]

secret=secretfield.getText().toString();

try {

Integer.parseInt(secret);

TalkToMothership talk = new TalkToMothership(domain);

talk.login(loginname, password);

String token = talk.getToken(flag_id, secret);

outputfield.setText("Token: " + token);

} catch(NumberFormatException e) {

outputfield.setText("Error: For your convinience the " +

"secret(seed) only consists of 4 digits!");

//[...]At this point you know that the secret to be guessed consists of four digits and the TalkToMothership class is responsible for communication to the web service. The class exposes two methods: one for the login and the other one (p_ublic String getToken(String flag_id, String secret)_) fires up two requests. It retrieves the mentioned time stamp and then after doing some magic crypto gets a valid flag from the web service. For a strong duty segregation the actual crypto of course resides in a separate class named UnsecurCrypto. The static method gets the time stamp and secret (as user input from the Android view) to do the following:

- Convert secret to hex

- Base64-encode the hex-secret

- ROT13 encoding/encryption of the secret

- Padding of the secret with 44 “a”s to match the length of time stamp

- XOR the padded secret with time stamp

- Base64-encode the result

Among a valid session ID (retrieved during login) this is the string which is sent to the web service. In case the secret was valid the response contains the corresponding FLAG, otherwise an error message. After you made your way through obfuscated Java code the reversing of the crypto method is probably a lot easier then the rest. In case you are still wondering why you couldn’t just reverse the Python web service: it contains the hashed result of the fourth operation (padding) which is compared later to prevent you from skipping the app.

Summary

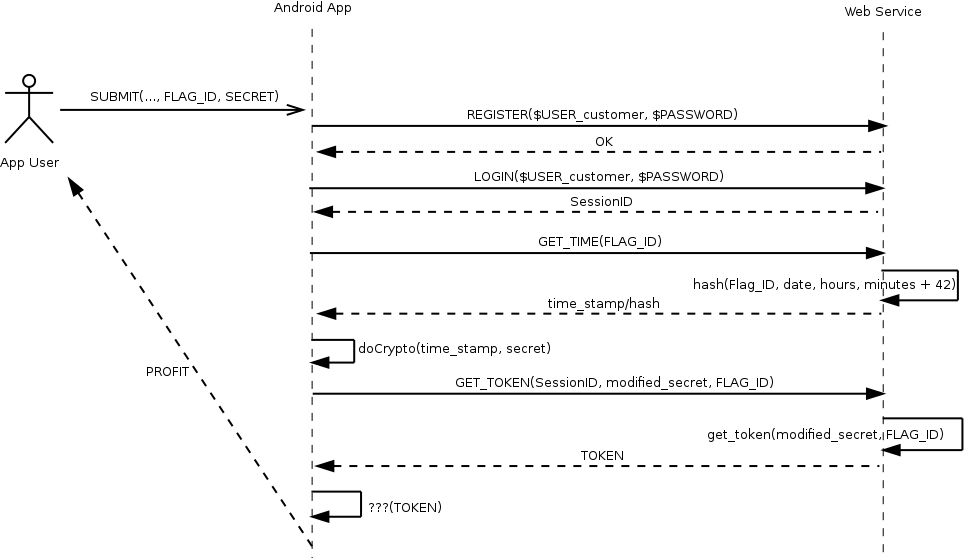

With this information and after carefully reading hints from the job openings and the customer area you figured out that you have to brute-force the secret reimplementing the crypto from the Android app. It becomes very obvious since the secret is not mentioned anywhere and is simple :-) The app description mentions “[…]For testing purposes there’s a FLAG_ID 424242 which you can use to test the service.[…]” so you have only one unknown variable during brute-force (waiting for valid flag IDs would be really mean since they change every couple of minutes). To recap what the Cpt Security Sparrow’s software ecosystem does consider the following illustration (kind of a sequence diagram).

As an attacker you have to replicate the Android app’s functionality in order to deliver a valid exploit. After getting a valid session you can use “42424242” as the FLAG_ID. To brute-force the original secret you have to execute the GET_TIME() and GET_TOKEN() requests until you receive {“424242”, “INVALID_TEST_TOKEN”} as response. If you wish to explore the functionality by yourself you can download cpt_sec_sparrow source of the submitted service and the Android app. Use the Flask’s build in debugging server by just running python2 uss.py and visiting http://localhost:8000 with your web browser. The only dependency is the flask Python egg. The app won’t work out of the box since it expects the web service to run as CGI-scripts. You have to adjust the URL inside TalkToMothership class to fix this (or setup a web server).

Cptn Security Sparrow’s App Store and the UnsecurID app was a joint work of the Ulm Security Sparrows. We send our greetings towards the two teams who solved the challenge. See you next CTF.